Christian Palestine: 4th - 7th century AD The adoption of Christianity as the state religion, by the emperor Constantine, gives Jerusalem a new status. Pilgrims begin to arrive, among them even the mother of the emperor, Helena, whose significant achievement - so the story goes - is to discover the actual or true cross on which Christ died. Pilgrims bring wealth, and the interest of the imperial family results in important new buildings. Constantine establishes the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, commemorating the departure of Christ from this earth; Helena builds a church in Bethlehem to do the same for his arrival. This region has a significance in the world again. The bishop of Jerusalem becomes a great dignitary, as the Patriarch of Palestine.

The adoption of Christianity as the state religion, by the emperor Constantine, gives Jerusalem a new status. Pilgrims begin to arrive, among them even the mother of the emperor, Helena, whose significant achievement - so the story goes - is to discover the actual or true cross on which Christ died. Pilgrims bring wealth, and the interest of the imperial family results in important new buildings. Constantine establishes the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, commemorating the departure of Christ from this earth; Helena builds a church in Bethlehem to do the same for his arrival. This region has a significance in the world again. The bishop of Jerusalem becomes a great dignitary, as the Patriarch of Palestine.

During these Christian centuries the might of neighbouring Persia remains a threat to the security of Palestine and Syria, though local unrest is more often the result of passionate disagreement over Christian doctrine.

However, the capture of Antioch by the Persian emperor Khosrau I in 540 is an unpleasant shock. It is also a foretaste of disastrous experiences at the hands of the Persians a few decades later. The Christian cities of the Middle East are caught up in the last great Persian onslaught against Byzantium, launched in the early 7th century by Khosrau II.

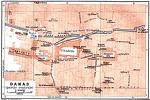

The first Christian city to fall to Khosrau's armies is Antioch, in 611. Damascus follows in 613. In the spring of 614 a Persian army enters Palestine and moves through the countryside, burning churches. Only the church built by St Helena in Bethlehem is spared; the Persians recognize themselves in the costumes of the Magi, seen bringing their gifts to the infant Jesus in a mosaic above the entrance.

The army reaches Jerusalem in April. The Patriarch urges the inhabitants to surrender, so as to avoid bloodshed, but they resist for a month. When the city falls, it is said that some 60,000 Christians are massacred and another 35,000 sold into slavery.

From the point of view of the Christian hierarchy, far away in Constantinople, the Persians commit one even greater affront. After sacking Jerusalem, they carry off to Ctesiphon the most holy relic of Christendom, the True Cross of Christ.

Its restoration to Jerusalem becomes an urgent matter of state.

Recovering the relic: AD 622-629

Under the emperor Heraclius, Byzantium has been quietly regaining its strength. In AD 622 Heraclius feels ready to take the field against the Persians. His successes are as rapid and spectacular as the reverses of the previous decade. By 624 he has swept through Asia Minor and Armenia to reach Azerbaijan, to the north of Persia between the Black Sea and the Caspian.

Here, as if avenging the violation of the True Cross, he destroys one of the most sacred fire temples of Zoroastrianism.

In the next few years the swings of fortune become even more extreme. In 626 a Persian army reaches the Bosphorus, but fails to cross the water to support a siege of Constantinople's massive walls by a barbarian horde of Slavs and Avars. In 627 a Byzantine army under Heraclius penetrates Mesopotamia far enough to defeat the Persians at Nineveh and destroy Khosrau's palace at Ctesiphon.

From a position of strength Heraclius negotiates the return of the True Cross. He takes it back to be displayed in Constantinople, and then personally returns it, in 629, to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. But the relic proves powerless against the next threat to Jerusalem in 638.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(46)

-

▼

February

(14)

- Palestina And Syria < 6 of 6 >

- Palestina And Syria < 5 of 6 >

- Palestina And Syria < 4 of 6 >

- Palestina And Syria < 3 of 6 >

- Palestina And Syria < 2 of 6 >

- Palestina And Syria < 1 of 6 >

- PALESTINE AND PHOENICIA

- Jews < Page 6 of 6 >

- Jews < Page 5 of 6 >

- Jews < Page 4 of 6 >

- Jews < page 3 of 6 >

- Jews < page 2 of 6 >

- Jews < Page 1 of 6 >

- Afghanistan

-

▼

February

(14)