Mamelukes and Mongols: AD 1250-1260 The decade beginning in 1250 provides a succession of dramatic events in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia. In 1250 the last sultan of Saladin's dynasty is murdered in Egypt by the slaves of the palace guard. This enables a Mameluke general, Aybak, to take power. He rules until 1257, when his wife has him killed in a palace intrigue. His place is immediately taken by another Mameluke general, Qutuz. In the following year, 1258, Baghdad and the caliphate suffer a devastating blow. Mongols, led by Hulagu, grandson of Genghiz Khan, descend upon the city and destroy it. The Middle East appears to be open to conquest and destruction.

The decade beginning in 1250 provides a succession of dramatic events in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia. In 1250 the last sultan of Saladin's dynasty is murdered in Egypt by the slaves of the palace guard. This enables a Mameluke general, Aybak, to take power. He rules until 1257, when his wife has him killed in a palace intrigue. His place is immediately taken by another Mameluke general, Qutuz. In the following year, 1258, Baghdad and the caliphate suffer a devastating blow. Mongols, led by Hulagu, grandson of Genghiz Khan, descend upon the city and destroy it. The Middle East appears to be open to conquest and destruction.

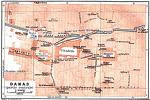

In 1259 Hulagu and the Mongols take Aleppo and Damascus. The coastal plain and the route south to Egypt seem open to them. But in 1260 at Ayn Jalut, near Nazareth, they meet the army of the Mameluke sultan of Egypt. It is led into the field by Baybars, a Mameluke general.

In one of the decisive battles of history Baybars defeats the Mongols. It is the first setback suffered by the family of Genghis Khan in their remorseless half century of expansion. This battle defines for the first time a limit to their power. It preserves Palestine and Syria for the Mameluke dynasty in Egypt. Mesopotamia and Persia remain within the Mongol empire.

Baybars and his successors: AD 1260-1517

Baybars is ruthless - in the best Mameluke tradition. Seized as a boy from the Kipchak Turks, north of the Caspian, he has been brought to Egypt as a slave. His talents have enabled him to rise to high command in the Mameluke army. In 1260, the year of his great victory at Ayn Jalut, he defeats and kills his own Mameluke sultan. He is proclaimed in his place by the army.

During his reign of seventeen years Baybars crushes the Assassins in their last strongholds in Syria, drives the crusaders from Antioch, and extends the rule of Egypt across the Red Sea to control the valuable pilgrim cities of Mecca and Medina.

In exercising this extensive rule, Baybars takes the precaution of pretending that he does so on behalf of an Abbasid refugee from the ruins of Baghdad - whom he acclaims as the caliph. His many successors maintain the same fiction. These Mameluke sultans are not a family line, like a traditional dynasty. They are warlords from a military oligarchy who fight and scheme against each other to be acclaimed sultan, somewhat in the manner of the later Roman emperors.

But they manage to keep power in their own joint hands until the rise of a more organized state sharing their own Turkish origins - the Ottoman empire.

The Ottomans, cautious about Mameluke military prowess, tackle other neighbouring powers such as the Persians before approaching Egypt. But in 1517 the Ottoman sultan, Selim I, reaches the Nile delta. He takes Cairo, with some difficulty, and captures and hangs the last Mameluke sultan.

Mameluke rule, spanning nearly three centuries, has been violent and chaotic but not uncivilized. Several of Cairo's finest mosques are built by Mameluke sultans, and for a while these rulers maintain Cairo and Damascus (500 miles apart) as twin capitals. A pigeon post is maintained between them, and Baybars prides himself on being able to play polo within the same week in the two cities.

The Ottoman centuries: AD 1516-1917

Ottoman rule over the region of Palestine and Syria lasts for four centuries from the arrival of the sultan and his army in 1516. The region is ruled for most of that period by a provincial administration in Damascus. From time to time there is unrest, turmoil and violence - but as if in a vacuum. Firm Ottoman control seals the area from outside influence or intrusion (apart from a few dramatic months in 1799, when Napoleon arrives in the district).

A longer and more significant interlude is the period from 1831 to 1840, when Mohammed Ali - the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt - seizes Palestine and Syria from his own master, the sultan.

The military campaign is conducted by Mohammed Ali's son, Ibrahim Pasha, who becomes governor general of the area. He rules rather better than the Ottoman administration, allowing a degree of modernisation. But Britain, Austria and Russia come to the aid of the sultan in 1840, forcing Mohammed Ali to withdraw his armies to Egypt.

During the following decades the most significant development is the beginning of European Jewish settlement in Palestine, from 1882. But it is World War I which changes the region out of recognition, ending the Ottoman centuries. British forces reach Palestine in 1917.

Sections are as yet missing at this point.

Sections Missing

Sections are as yet missing at this point

Arabia and Palestine: AD 1916

When the Turks enter the war, in 1914, the hereditary emir of Mecca (Husayn ibn Ali) sees a chance of extricating his territory from Ottoman rule. He secretly begins negotiating with the British. By June 1916 he is ready to launch an Arab revolt along the Red Sea coast.

The most effective part of this uprising is conducted by Faisal, one of Husayn's sons, in conjunction with T.E. Lawrence, a young British officer seconded for the purpose. Together they attack the most strategically important feature in the region, the railway which runs south from Damascus, through Amman and Ma'an, to Medina. This is the only route by which the Turks can easily send reinforcements to Arabia.

The policy succeeds and by the summer of 1917 the Arabs have moved far enough north to capture Aqaba. This is achieved on July 6 in a dramatic raid by Lawrence and some Arab chiefs with a few hundred of their tribesmen. Together they kill or capture some 1200 Turks at a cost of only two of their own lives.

The port of Aqaba occupies an important position at the head of the gulf of the same name. It offers relatively easy access up towards the Dead Sea. Faisal's army is now well placed to support a British thrust into Palestine, by operating from the desert region of the Negev to bring pressure on the eastern flank of the Turks.

During the winter of 1916 the British have been laying a railway along the northern coast of the Sinai peninsula. This makes possible an attack on Gaza, the gateway into Palestine. But on two separate occasions - in March and April 1917 - the campaign is seriously bungled. As a result a new commander, Edmund Allenby, is brought in.

Allenby succeeds in taking Gaza on November 7. He follows this with the capture of Jerusalem a month later, on December 9. Meanwhile Britain's fortunes in Mesopotamia have also been transformed by a new commander, Stanley Maude. Maude retakes Kut on 24 February 1917 and captures Baghdad on March 11.

So by the end of 1917 the Allies, occupying both Jerusalem and Baghdad, have completed half the necessary task in the Middle East. But they are still a long way from the frontier of Turkey itself. On the Mediterranean front Damascus and Aleppo lie ahead, in Mesopotamia there is still Mosul to be taken. And even then there is the almost impenetrable terrain of Anatolia before one can reach Istanbul.

With massive armies confronting each other on the western front, this all seems a long way from the centre of the action. But this year of 1917 has meanwhile brought two major developments, in the USA and Russia, which in their very different ways profoundly alter the equation of the war.

This History is as yet incomplete.

Palestina And Syria < 6 of 6 >

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)