Uncharted territory: to the 19th century AD In the uncharted centuries of prehistory, Tanzania is criss-crossed by tribal trade routes linking the Great Lakes (Victoria and Tanganyika) with the coast. These are the same routes along which Arab traders subsequently move inland, searching for slaves and ivory.

In the uncharted centuries of prehistory, Tanzania is criss-crossed by tribal trade routes linking the Great Lakes (Victoria and Tanganyika) with the coast. These are the same routes along which Arab traders subsequently move inland, searching for slaves and ivory.

In a second wave of penetration by outsiders, Europeans use Bagamoyo (opposite Zanzibar) as their starting point for exploration inland. Burton and Speke do so in 1856, as does Stanley in 1871 and again in 1874. But the most significant visitor to the region turns out to be Karl Peters, a young man with a feverish enthusiasm for the notion of a German empire.

Peters, with two companions, spends a few weeks at the end of 1884 moving at frantic speed within the sultan of Zanzibar's mainland territories. The trio arrive in each new region with blank treaty forms and German flags. They fill in the local chief's name and persuade him to make his mark on the document and to run up a flag. Then they move on. Grievously under-equipped and soon short of food, they only just manage to make their way back to the coast.

But Peters, returning to Berlin, has an exciting proposition to put to Bismarck - who is himself in high imperial mood, with his Berlin colonial conference still in progress. A German east African colony, Peters tells him, is there for the taking.

In February 1885 Bismarck grants Peters a charter for an East African protectorate, but the fact is kept secret until the colonial conference has ended. Meanwhile Peters recruits more agents in Africa to continue the work of distributing treaty forms. Their instructions are to be schnell, kühn, rücksichtslos (swift, daring, ruthless).

When the sultan of Zanzibar hears of the proposed protectorate on his territory, he sends a protest to the German emperor. It reaches Berlin in May. Bismarck asks Peters what the response should be. Peters replies that there is a lagoon facing the sultan's palace in Zanzibar, deep enough for warships to anchor in.

A German-British carve up: AD 1885-1886

On 7 August 1885 five German warships steam into the lagoon of Zanzibar and train their guns on the sultan's palace. They have arrived with a demand from Bismarck that Sultan Barghash cede to the German emperor his mainland territories or face the consequences.

But in the age of the telegram, gunboat diplomacy is no longer a local matter. This crisis is immediately on desks in London. Britain, eager not to offend Germany, suggests a compromise. The two nations should mutually agree spheres of interest over the territory stretching inland to the Great Lakes. This plan is accepted before August is out.

The embarrassed British consul finds himself under orders from London to persuade the sultan to sign an agreement ceding the lion's share of his mainland territory, with the details still to be decided. In September the German gunships begin their journey home. A joint Anglo-German boundary commission starts work in the interior.

By November 1886 the task is done and the result is agreed with the other main colonial power, France. The sultan is left a strip ten miles wide along the coast. Behind that a line is drawn to Mount Kilimanjaro and on to Lake Victoria at latitude 1° S. The British sphere of influence is to be to the north, the German to the south. The line remains to this day the border between Kenya and Tanzania.

German East Africa: AD 1886-1916

The administration of the territory in the agreement of 1886 is handed over to Karl Peters' German East Africa Company. The company extends its territory to the sea from 1888, by buying a lease of the coastal strip which was left in the sultan of Zanzibar's possession. But local resentment leads to a Muslim uprising in that year which is only suppressed after the arrival of German troops (assisted on this occasion by the British navy).

The inadequacy of the company causes the German government to take direct control in 1891. But Karl Peters retains his involvement, being appointed imperial commissioner.

There follow two decades in which the German authorities make considerable efforts to develop their east African colony. A railway is built from Dar es Salaam to Tabora and then on to Ujiji. New crops, such as sisal and cotton, are introduced and prove very successful - as also is the development of coffee plantations on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro.

But this energetic German presence is profoundly resented by the African tribes, particularly when the harsh methods of forced labour are used in the cultivation of the new and alien crops. The result, in 1905, is a widespread popular rebellion which becomes known as the Maji-Maji rising.

Maji is the Swahili for 'water'. The rising gets its name because the belief spreads among the African workers that a magic potion of water, castor oil and millet seeds can turn German bullets to water. In August 1905 the drums begin to broadcast the news that cotton plants are being pulled up rather than tended, in a symbolic gesture of resistance.

The excitement spreads throughout much of the colony, as people drink the potion and set off on a rampage wearing headbands woven from the stalks of millet, the indigenous crop. Soon, inevitably, there are murderous attacks on Germans and the burning of their houses.

Reinforcements arrive from Germany in October 1905, by which time many of the Maji-Maji have already begun to discover that German bullets do not turn to water. The German commander, General von Götzen, uses a strategy hardly more humane than that of his colleague von Trotha in Namibia, whose brutality has caused an international outcry only a year previously.

Von Götzen decides that in the long term only famine will bring these rebellious workers to heel. He instructs his troops to move through the country destroying crops, removing or burning any grain already harvested, and putting entire villages to the torch.

It is estimated that about 250,000 Africans die in the resulting famine. German East Africa, like German South West Africa, acquires in its early years a besmirched colonial record. Meanwhile Karl Peters, the originator of this colony, has in 1897 been tried and convicted in a Potsdam court for brutal offences committed in Africa. They include his response to the suspicion that one of his servants may have slept with his African mistress. The young girl is flogged and then both are hanged.

These scandals shock Berlin sufficiently for reforms in colonial policy to be hastily put in place. But any likely benefit is cut short by the onset of World War I. Early in 1916 British forces move south from Kenya to occupy German East Africa.

British Mandate: AD 1919-1962

After the end of the war the treaty of Versailles, in 1919, grants Britain a League of Nations mandate to govern the former German East Africa - which now acquires a new name, Tanganyika.

British policy from the 1920s onwards is to encourage indigenous African administration along traditional lines, through local councils and courts. A legislative council is also established in Dar es Salaam, but African members are not elected to this until after World War II. By then local political development is an obligation under the terms of UN trusteeship, in which Britain places Tanganyika in 1947.

During the 1950s a likely future leader of Tanganyika emerges in the person of Julius Nyerere. Son of a chief, a convert to Roman Catholicism while studying at Makerere college in Uganda, then an undergraduate for three years in Edinburgh university, Nyerere returns to Tanganyika in 1953.

He immediately founds a political party, TANU or the Tanganyika African National Union (evolving it from an earlier and defunct Tanganyika African Association). From the start its members feature prominently in elections to the legislative assembly. When independence follows, in 1961, Nyerere becomes the new nation's prime minister. In 1962 Tanganyika adopts a republican constitution and Nyerere is elected president.

Republic of Tanzania: AD 1964-1985

In 1964 Nyerere reaches an agreement with Abeid Karume, president of the offshore island of Zanzibar which has been so closely linked in its history to the mainland territory of Tanganyika. The two presidents sign an act of union, bringing their nations together as the United Republic of Tanzania. Nyerere becomes president of the new state, with Karume as his vice-president.

Nyerere, by instinct an idealistic socialist, guides his country along lines which often have a utopian touch. Local self-sufficiency is emphasized. Traditional and simple solutions are sought for local problems rather than relying on technological foreign imports. Great importance is placed on education and literacy, in which excellent results are achieved.

Nyerere declares his political creed in a document of 1967 known as the Arusha Declaration. This announces the introduction of a socialist state and is accompanied by the nationalization of key elements in the economy. With such policies Nyerere inevitably has to rely on help from the eastern bloc, and in particular China. Nevertheless he is able to maintain his declared international stance of non-alignment.

The Arusha Declaration puts agriculture at the centre of the national economy and introduces a programme of 'villagization' - meaning the moving of peasant families into cooperative villages where they can supposedly work together more productively.

As elsewhere where such cooperatives have been tried (in particular Mao Tse-tung's China, a source of inspiration to Nyerere), they prove both unpopular and inefficient. When Nyerere relinquishes executive power voluntarily in 1985 (a rare act in modern African history, and certainly one with no appeal to Mao), he admits that his economic policies have failed.

But in his twenty-three years in office he has established an impressive reputation as an independent and free-thinking African statesman - willing to sever relations with the UK (1965-8) because of British acceptance of racist Rhodesia and South Africa, but also taking on the OAU (as when he recognizes Biafra's secession in 1968).

Chama Cha Mapinduzi: from AD 1977

From 1965 each part of the union has only one political party, but they are different parties - TANU in Tanganyika and ASP (Afro-Shirazi Party) in Zanzibar. In 1977 they merge as the CCM or Chama Cha Mapinduzi (Revolutionary Party).

When Nyerere stands down as president, in 1985, he remains chairman of the CCM and as such retains an important voice in the formulation of general policy. For the executive post of president the party puts forward only one candidate, Ali Hassan Mwinyi. However, by the early 1990s there is irresistible pressure - here as elsewhere in Africa - for the introduction of multiparty democracy.

President Mwinyi promulgates a new democratic constitution in 1992, with the stipulation that political parties will only be registered if they are active in both Tanganyika and Zanzibar and if they are not identified with specific religious, regional, tribal or racial groups.

Elections are held in 1995. The CCM just wins in Zanzibar, where opposition anger at electoral malpractice disrupts polital life for the rest of the decade. In Tanganyika the CCM candidate Benjamin Mkapa is elected president of the union, but only after all his rivals have withdrawn from the race alleging ballot-rigging.

During the 1990s very great strain is placed on an already impoverished Tanzania by the ethnic conflicts over the border in Rwanda and Burundi. During a single 24-hour period in 1994 as many as 250,000 Rwandan refugees stream into Tanzania. Eventually the total is 550,000 from Rwanda and 100,000 from Burundi. Many of them are still in Tanzania at the end of the decade.

In Dar es Salaam a hopeful sign is the progress of an anti-corruption campaign launched by President Mkapa. In 1997 more than 1500 civil servants are dismissed on these grounds.

Tanzania

The Divine Art of Tapestries < Page 2 of 2 >

Like video and unlike painting, tapestry is a digital medium. Painters compose images in lines and brushstrokes of any variety they choose, but tapestries are composed point by point. The visual field of a tapestry is grainy, and has to be. Every stitch is like a pixel.

Like video and unlike painting, tapestry is a digital medium. Painters compose images in lines and brushstrokes of any variety they choose, but tapestries are composed point by point. The visual field of a tapestry is grainy, and has to be. Every stitch is like a pixel.

Weaving tapestries is easiest when the objects depicted are flat, when the patterns are strong and the color schemes are simple. Three-dimensional objects, fine shadings and subtle color gradations make the work much harder. Artists like Raphael and Rubens made no concessions to the difficulties, pushing the greatest workshops to surpass themselves. But there have been train wrecks, too. For the Spanish court, Goya produced some five-dozen rococo cartoons of daily life that are counted among the glories of the Prado, in Madrid. In weavings, the same scenes appear grotesque, almost nightmarish, the faces pulled out of shape by the unevenness of the texture, eyes bleary for lack of definition.

“We know so little about the weavers,” says Thurman. “Quality depends on training. As the centuries marched on, there was always pressure for faster manufacture and quicker techniques. After the 18th century, there was a vast decline.” The Chicago show cuts off before that watershed.

After January 4, everything goes back into storage. “Yes,” says Thurman, “that’s an unfortunate fact. Due to conservation restrictions, tapestries should not be up more than three months at a time.” For one thing, light degrades the silk that is often the support for the entire textile. But there are also logistical factors: in particular, size. Tapestries are typically very large. Until now, the Art Institute has had no wall space to hang them.

The good news is that come spring, the paintings collection will migrate from the museum’s historic building to the new Modern Wing, designed by Renzo Piano, freeing up galleries of appropriate scale for the decorative arts. Tapestries will be integrated into the displays and hung in rotation. But to have 70 prime pieces on view at once? “No,” says Thurman, “that can’t be repeated immediately.”

The Divine Art of Tapestries < Page 1 of 2>

The Divine Art of Tapestries

The long-forgotten art form receives a long overdue renaissance in an exhibit featuring centuries-old woven tapestries

* By Matthew Gurewitsch

* Smithsonian.com, December 23, 2008 Apart from crowd-pleasers such as the Dame à la Licorne (Lady with the Unicorn) series at the Musée Cluny in Paris and the “Unicorn” group at the Cloisters in New York City, tapestries have been thought of throughout the 20th century as dusty and dowdy -- a passion for out-of-touch antiquarians. But times are changing.

Apart from crowd-pleasers such as the Dame à la Licorne (Lady with the Unicorn) series at the Musée Cluny in Paris and the “Unicorn” group at the Cloisters in New York City, tapestries have been thought of throughout the 20th century as dusty and dowdy -- a passion for out-of-touch antiquarians. But times are changing.

“The Divine Art: Four Centuries of European Tapestries in the Art Institute of Chicago,” on view at the Art Institute through January 4 and documented in a sumptuous catalog, is the latest in a flurry of recent exhibitions to open visitors’ eyes to the magnificence of a medium once prized far above painting. In Mechelen, Belgium, a landmark show in 2000 was dedicated to the newly conserved allegorical series Los Honores, associated with the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In 2004, the National Tapestry Gallery in Beauvais, France, mounted “Les Amours des Dieux” (Loves of the Gods), an intoxicating survey of mythological tapestries from the 17th to 20th centuries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art scored triumphs with “Tapestry in the Renaissance: Art and Magnificence” in 2002, billed as the first major loan show of tapestries in the United States in 25 years, and with the encore “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” in 2007.

Highlights of the current show at the Art Institute include a rare Italian Annunciation from around 1500, a Flemish Battle of Actium from a 17th-century series illustrating the story of Caesar and Cleopatra, and an 18th-century French tapestry titled The Emperor Sailing, from The Story of the Emperor of China.

“We have a phenomenal collection, and it’s a phenomenal show,” says Christa C. Mayer Thurman, curator of textiles at the Art Institute. “But I don’t like superlatives unless I can document them. I feel safer calling what we have a `medium-size, significant collection.’”

Though the Art Institute does not pretend to compete with the Met or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, let alone the Vatican or royal repositories in Europe, it does own about 100 tapestries of excellent quality. On view in the show are 70 pieces, all newly conserved over the past 13 years, after decades in storage. “Please use the word conservation,” says Thurman, “not restoration. There’s a vast difference. In conservation, we conserve what is there. We don’t add and we don’t reweave.”

The value of a work of art is a function of many variables. From the Middle Ages to the Baroque period, tapestry enjoyed a prestige far beyond that of painting. Royalty and the church commissioned whole series of designs—called cartoons—from the most sought-after artists of their times: Raphael, Rubens, Le Brun. Later artists from Goya to Picasso and Miró and beyond have carried on the tradition. Still, by 20th-century lights, tapestries fit more naturally into the pigeonhole of crafts than of fine arts.

Thus the cartoons for Raphael’s Acts of the Apostles, produced by the actual hand of the artist, are regarded as the “real thing,” whereas tapestries based on the cartoons count as something more like industrial artifacts. (The cartoons are among the glories of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). It only adds to contemporary misgivings about the medium to learn that cartoons could be “licensed” and woven in multiples, by different workshops, each time at staggering expense—as happened with both Los Honores and The Acts of the Apostles.

In their Golden Age, however, tapestries were seen to offer many advantages. They are portable, for one thing, as frescoes and wall paintings on a similar scale are not. For another, tapestries helped take the edge off the cold in large, drafty spaces. They had snob appeal, since only the richest of the rich could afford them. To hang tapestries was to show that you not only could appreciate the very best but that cost was no object. The materials alone (threads of silk and precious metals) could be worth a fortune, not to mention the massive costs of scarce, highly skilled labor. Whereas any dabbler could set up a studio and hang out a shingle as a painter, it took James I to establish England’s first tapestry factory at Mortlake, headed by a master weaver from Paris and a work force of 50 from Flanders.

Muhammad

Mecca and Muhammad: AD c.570 - 622 A child, Muhammad, is born in a merchant family in Mecca. His clan is prosperous and influential, but his father dies before he is born and his mother dies when the boy is only six.

A child, Muhammad, is born in a merchant family in Mecca. His clan is prosperous and influential, but his father dies before he is born and his mother dies when the boy is only six.

Entrusted to a Bedouin nurse, Muhammad spends much of his childhood among nomads, accompanying the caravans on Arabia's main trade route through Mecca.

A widow, Khadija, considerably older than Muhammad, has sufficient faith in him to entrust him with her business affairs; and when he is twenty-five, they marry. For the next fifteen years or so he lives the life of a prosperous merchant. But he develops one habit untypical of merchants.

From time to time he withdraws into the mountains to meditate and pray. In about the year 610 he has a vision which changes his life; and changes world history.

It is on Mount Hira, according to tradition, that the archangel Gabriel appears to Muhammad. He describes later how he seemed to be grasped by the throat by a luminous being, who commanded him to repeat the words of God. On other occasions Muhammad often has similar experiences (though there are barren times, and periods of self doubt, when he is sustained only by his wife Khadija's unswerving faith in him).

From about 613 Muhammad preaches in Mecca the message which he has received.

Muhammad's message is essentially the existence of one God, all-powerful but also merciful, and he freely acknowledges that other prophets - in particular Abraham, Moses and Jesus - have preached the same truth in the past.

But monotheism is not a popular creed with those whose livelihood depends on idols. Muhammad, once he begins to win converts to the new creed, makes enemies among the traders of Mecca. In 622 there is a plot to assassinate him. He escapes to the town of Yathrib, about 300 kilometres to the north.

Muhammad and the Muslim era: from AD 622

The people of Yathrib, a prosperous oasis, welcome Muhammad and his followers. As a result, the move from Mecca in 622 comes to seem the beginning of Islam.

The Muslim era dates from the Hegira - Arabic for 'emigration', meaning Muhammad's departure from Mecca. In the Muslim calendar this event marks the beginning of year 1.

Yathrib is renamed Madinat al Nabi, the 'city of the prophet', and thus becomes known as Medina. Here Muhammad steadily acquires a stronger following. He is now essentially a religious, political and even military leader rather than a merchant (Khadija has died in 619).

He continues to preach and recite the words which God reveals to him. It is these passages, together with the earlier revelations at Mecca, which are written down in the Arabic script by his followers and are collected to become the Qur'an - a word (often transliterated as Koran) with its roots in the idea of 'recital', reflecting the oral origin of the text. The final and definitive text of the Qur'an is established under the third caliph, Othman, in about 650.

The Muslims and Mecca: AD 624-630

Relations with Mecca deteriorate to the point of pitched battles between the two sides, with Muhammad leading his troops in the field. But in the end it is his diplomacy which wins the day.

He persuades the Meccans to allow his followers back into the city, in 629, to make a pilgrimage to the Kaaba and the Black Stone.

On this first Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, Muhammad's followers impress the local citizens both by their show of strength and by their self-control, departing peacefully after the agreed three days. But the following year the Meccans break a truce, provoking the Muslims to march on the city.

They take Mecca almost without resistance. The inhabitants accept Islam. And Muhammad sweeps the idols out of the Kaaba, leaving only the sacred Black Stone.

An important element in Mecca's peaceful acceptance of the change has been Muhammad's promise that pilgrimage to the Kaaba will remain a central feature of the new religion.

So Mecca becomes, as it has remained ever since, the holy city of Islam. But Medina is by now where Muhammad and his most trusted followers live. And for the next few decades Medina will be the political centre of the developing Muslim state.

Muhammad lives only two years after the peaceful reconciliation with Mecca. He has no son. His only surviving children are daughters by Khadija, though since her death he has married several younger women, among whom his favourite is A'isha.

Muhammad and the caliphate: from AD 632-656

There is no clear successor to Muhammad among his followers. The likely candidates include Abu Bakr (the father of Muhammad's wife A'isha) and Ali (a cousin of Muhammad and the husband of Muhammad's daughter Fatima). Abu Bakr is elected, and takes the title 'khAlifat rasul-Allah'.

The Arabic phrase means 'successor of the Messenger of God'. It will introduce a new word, cAliph, to the other languages of the world.

Ismailis

The Ismaili sect: from the 9th century AD The Ismailis break away from the main body of the Shi'as on the question of the line of imams in succession to Muhammad (precisely the issue on which the Shi'as and Sunnis have broken away from each other ). Between Shi'as and Ismailis the dispute concerns the seventh imam, in the later years of the 8th century. The Shi'as give this position to Musa; the Ismailis support his elder brother, Ismail. By the 9th century the Ismailis are an identifiable sect, based in Syria and strongly opposed to the rule of the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad. In the 10th century they establish their own rule over the entire coast of north Africa, technically part of the caliphate.

The Ismailis break away from the main body of the Shi'as on the question of the line of imams in succession to Muhammad (precisely the issue on which the Shi'as and Sunnis have broken away from each other ). Between Shi'as and Ismailis the dispute concerns the seventh imam, in the later years of the 8th century. The Shi'as give this position to Musa; the Ismailis support his elder brother, Ismail. By the 9th century the Ismailis are an identifiable sect, based in Syria and strongly opposed to the rule of the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad. In the 10th century they establish their own rule over the entire coast of north Africa, technically part of the caliphate.

The Fatimid dynasty: AD 909-1171

An Ismaili leader, Ubaydulla, conquers in 909 a stretch of north Africa, displacing the Aghlabids in Kairouan. He founds there a dynasty known as Fatimid - for he claims to be a caliph in the Shi'a line of descent from Ali and Fatima his wife, the daughter of Muhammad.

Sixty years later, in 969, a Fatimid army conquers Egypt, which now becomes the centre of a kingdom stretching the length of the north African coast. A new capital city is founded, adjoining a Muslim garrison town on the Nile. It is called Al Kahira ('the victorious'), known in its western form as Cairo. In the following year, 970, the Fatimids establish in Cairo the university mosque of Al Azhar which has remained ever since a centre of Islamic learning.

At the height of Fatimid power, in the early 11th century, Cairo is the capital of an empire which includes Sicily, the western part of the Arabian peninsula (with the holy places of Mecca and Medina) and the Mediterranean coast up to Syria.

A century later the authority of the Ismaili caliphs has crumbled. There is little opposition in 1171 when Saladin, subsequently leader of the Islamic world against the intruding crusaders, deposes the last of the Fatimid line. And there is no protest when Saladin has the name of the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad included in the Friday prayers in Cairo's mosques. After a Shi'a interlude, Egypt is back in the Sunni fold.

The collapse of the Fatimid caliphate does not mean the end of the political influence of the Ismailis. There has been a dispute in 1094 over who shall be caliph. The Fatimids in Egypt select one of two brothers. Ismailis in Persia and Syria prefer the other, by the name of Nizar.

The Nizari become a separate and extremely alarming sect. From the late 11th century they begin seizing territory in northern Persia. They make a religious virtue of terrorism and murder in pursuit of their ends. They are known to history as the Assassins.

Assassins: 11th - 13th century

It is not known why their contemporaries give the name Assassins to the Nizari Ismailis who become promiment in the 11th century. All that is certain is that the political activities of the Nizari amply justify the subsequent use of 'assassin' in its modern meaning. (The old theory that the word comes from hashish, which the Assassins supposedly use to get in the mood for murder, derives from Marco Polo and other western writers but seems to have little basis.)

The Assassins first show their hand when they begin to seize strongholds in Persia in the late 11th century, particularly the almost impregnable fortress of Alamut. In the 12th century they also acquire bases in Syria.

The Assassins train terrorists and employ a network of secret agents in the camps and cities of their enemies. These enemies are legion. Foremost among them are the Seljuk Turks and the caliphs in Baghdad (the Assassins murder two caliphs). But the terrorists also act against their fellow Ismailis, the Fatimids in Cairo. They assassinate at least one prominent crusader. Most eccentrically of all, they make two attempts on the life of Saladin.

No way is found to eliminate this troublesome sect until the Assassins are finally crushed between two great rival powers in the 12th century - the Mameluke sultans of Egypt and the Mongols, led by Hulagu.

The Aga Khan: from 1818

Deprived of their military power, the Assassins survive in Persia as the Nizari Ismaili, a minor heretical sect of Shi'ite Islam. Their leaders still claim descent, through Nizar, from Ali and Fatima. In 1818 one of them is granted the title Aga Khan by the shah of Persia.

In 1840, after an abortive uprising against the next shah, this first Aga Khan flees to India. There he and his descendants remain leaders of an Ismaili community numbered, in Syria, Iran, Pakistan, India and elsewhere, in several millions. The present Aga Khan, born in 1946, is only the fourth in the line.

Aegean Civilization

The missing Minoans: 20th - 15th century BC It is astonishing that history should lose all track of a civilization which lasts for six centuries, makes superb ceramics and metalwork, trades extensively over a wide region, and houses its rulers in palaces elaborately decorated with superb fresco paintings. Yet this has been the case with the Minoans in Crete, until the excavation of Knossos.We still know little more about them than is suggested by Minoan art and artefacts. It is typical that the name they have been given derives from a figure of myth rather than history - Minos, the legendary king of Crete whose pet creature is the Minotaur, a monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull which feeds on young human flesh.

It is astonishing that history should lose all track of a civilization which lasts for six centuries, makes superb ceramics and metalwork, trades extensively over a wide region, and houses its rulers in palaces elaborately decorated with superb fresco paintings. Yet this has been the case with the Minoans in Crete, until the excavation of Knossos.We still know little more about them than is suggested by Minoan art and artefacts. It is typical that the name they have been given derives from a figure of myth rather than history - Minos, the legendary king of Crete whose pet creature is the Minotaur, a monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull which feeds on young human flesh.

Three very similar palaces have been excavated in Crete from the Minoan period - at Knossos, Mallia and Phaistos. Built from around 2000 BC, each is constructed round a large public courtyard; each has provision for the storage of large quantities of grain; each is believed to be the administrative centre for a large local population. The number at Knossos has been variably estimated as between 15,000 and 50,000 people.

Administrative records and accounts are kept on clay tablets in a script as yet undeciphered (it is known as Linear A). Archaeological discoveries reveal that trade is carried on round the entire Mediterranean coast from Sicily in the west to Egypt in the southeast.

Overseas there are outposts of Minoan culture. It is not known whether they are colonies or more in the nature of trading partners, influenced by the culture of Crete. Notable among them is the city of Akrotiri, on the island of Thera. Its houses, apparently those of rich merchants, have survived with their frescoes intact. Several of the houses stand to a height of three storeys, with their floors still in place.

The reason for their preservation is the eruption of the island's volcano in about 1525 BC. Like Pompeii a millennium and a half later, Akrotiri is pickled in volcanic ash.

Defensive walls are notably absent in Minoan Crete, as also are paintings of warfare. This seems to have been a peaceful as well as a prosperous society. But its end is violent. In about 1425 BC all the towns and palaces of Crete, except Knossos itself, are destroyed by fire.

It is not known whether this is a natural disaster, which gives Greeks from the mainland their chance, or whether Greek invaders destroy Minoan Crete - keeping only the main palace for their own use. But it is certain that the next generation of rulers introduce the culture of mainland Mycenae, and they keep their accounts in the Mycenaean script - Linear B. It seems probable that a Mycenaean invasion ends Minoan civilization.

The first Greek civilization: from the 16th century BC

The discovery that Linear B is a Greek script places Mycenae at the head of the story of Greek civilization. Its right to this place of honour is reinforced in legend and literature. The supposed occupants of the Mycenaean palaces are the heroes of Homer's Iliad.

Archaeology reveals the rulers of these early Greeks to have been as proud and warlike as Homer suggests.

Their fortress palaces are protected by walls of stone blocks, so large that only giants would seem capable of heaving them into place. This style of architecture has been appropriately named Cyclopean, after the Cyclopes (a race of one-eyed giants encountered by Odysseus in the Odyssey). The walls at Tiryns, said in Greek legend to have built by the Cyclopes for the legendary king Proteus, provide the most striking example.

At Mycenae it is the gateway through the walls which proclaims power, with two great lions standing above the massive lintel.

Royal burials at Mycenae add to the impression of a powerful military society. The tombs of the 16th century (known as 'shaft graves' because the burial is at the bottom of a deep shaft) contain a profusion of bronze swords and daggers, of a kind new to the region, together with much gold treasure, including death masks of the kings.

By the 14th century the graves themselves become more in keeping with the status of their occupants, with the development of the tholos or 'beehive' style of tomb. The most impressive is the so-called Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae, with its high domed inner chamber (independently pioneered in Neolithic western Europe 2500 years previously).

The earliest known suit of armour comes from a Mycenaean tomb, at Dendra. The helmet is a pointed cap, cunningly shaped from slices of boar's tusk. Bronze cheek flaps are suspended from it, reaching down to a complete circle of bronze around the neck. Curving sheets of bronze cover the shoulders. Beneath them there is a breast plate, and then three more circles of bronze plate, suspended one from the other, to form a semi-flexible skirt down to the thighs. Greaves, or shinpads of bronze, complete the armour.

The Mycenaean warrior's weapons are a bronze sword and a bronze-tipped spear. His shield is of stiff leather on a wooden frame. Similar weapons are used, several centuries later, by the Greek hoplites.

Trade and conquest: 13th - 12th century BC

By the 13th century Mycenaean rulers control to varying degrees the whole of the Peloponnese, together with the eastern side of mainland Greece as far north as Mount Olympus, the large islands of Crete and Rhodes and many smaller islands. This is indeed a civilization which spreads around and through most of the Aegean.

Mycenaeans trade the length of the Mediterranean, from the traditional markets of the eastern coasts to new ones as far away as Spain in the west. They also have long-range trading contacts with Neolithic societies in the interior of Europe.

In the latter half of the 13th century, according to well-established oral tradition, the rulers of Mycenaean Greece combine forces to assault a rich city on the other side of the Aegean Sea. The city is Troy. Some four centuries later the oral tradition will be written down as the Iliad.

In Homer's poem it takes many years before Troy is finally subdued. If there is truth in this, the war perhaps fatally weakens the Greeks. Certainly archaeology reveals that the successful Mycenaean civilization comes to an abrupt end not very much later - in about 1200 BC.

The sudden destruction of Mycenaean palaces in Greece is part of a wider pattern of chaos in the eastern Mediterranean. As far away as Egypt, the pharaohs fight off invasion by raiders whom they describe as people 'from the sea'. It is a mystery, then as now, exactly where these predators come from.

The most likely answer is the southern and western coasts of Anatolia. The rulers of Anatolia, the Hittites, are among their victims. So also are the communities of the eastern Mediterranean, where some of the Sea Peoples settle - to become known as the Philistines.

Doric and Ionic: from the 12th century BC

In muted form Mycenaean Greece survives this first assault. But it suffers a final blow later in the 12th century at the hands of the Dorians - northern tribesmen, as yet uncivilized, who speak the Doric dialect of Greek. The Dorians move south from Macedonia and roam through the Peloponnese. They have the advantage of iron technology, which helps them to overwhelm the Bronze Age Mycenaeans.

The Dorian incursion plunges Greece into a period usually referred to as a dark age. But Dorian military traditions survive to play a profound part in the heyday of classical Greece. The ruthlessly efficient Spartans will claim the Dorians as their ancestors, and model themselves upon them.

The rival tradition in classical Greece is linked with Athens, an outpost of Mycenaean culture. Athens successfully resists the Dorians and becomes something of a place of refuge for those fleeing the invaders.

With the encouragement of Athens, from about 900 BC, non-Dorian Greeks migrate to form colonies on the west coast of Anatolia. These colonies eventually merge to form Ionia (Ionic is the dialect spoken by the Athenians and by many other Greek tribes). In subsequent centuries Ionia, with Athens, becomes a cradle of the classical Greek civilization. So there is a genuine continuity from Mycenae. It is reflected in the romantic idea of Mycenaean Greeks expressed by Homer - himself probably a native of Ionia.

Arianism

Alexandria and Arius: AD 323-325 The heresy associated with the name of Arius, a priest in Alexandria, is the most significant in the history of Christianity. It concerns the mystery at the very heart of the religion - the Trinity.

The heresy associated with the name of Arius, a priest in Alexandria, is the most significant in the history of Christianity. It concerns the mystery at the very heart of the religion - the Trinity.

The problem for the early church has been that the Gospels talk of God and of Jesus (who describes God as his Father) and, more occasionally, of the Holy Spirit. But they do not explain how they relate to one another. All three seem to be divine, and yet - as a sect of monotheistic Judaism - early Christians know for sure that they worship only one God. How can this be? The concept of the Trinity, three in one and one in three, gradually emerges as the best answer. But it begs many questions.

Only if the three are equal can they be aspects of one god. Yet if God creates Jesus, he clearly has some sort of priority. On the other hand if God does not create Jesus, he can hardly be his Father. This is the problem which concerns Arius, who asks in particular whether there was ever a time when God existed but Jesus, as yet, did not. He concludes that there was such a time ('there was when he was not'). Jesus is therefore less than fully divine.

Even so, Arius agrees that it is right to worship Jesus. This reopens the door to polytheism, and in 323 the bishop of Alexandria dismisses his troublesome priest. The dispute rapidly escalates. In 325 Constantine intervenes, summoning a council at Nicaea.

Nicaea and orthodoxy: AD 325

More than 200 bishops, mainly from the eastern parts of the empire, arrive at Nicaea for the council. They meet in Constantine's palace, and the emperor himself presides over many of the discussions. His authority is purely political; though an undoubted supporter of Christianity, he has not yet been baptized.

The alarming presence of the emperor helps the bishops to reach a conclusion more emphatic than is justified by the range of their opinions. The crack opened wide by Arius seems to be firmly closed when it is announced at Nicaea that the Father and the Son are of the same substance (homo-ousios in Greek).

Between two councils: AD 325-381

During the lifetime of those who gather at Nicaea in AD 325 Arianism remains a controversial issue. Before the end of Constantine's reign Arius himself is brought back from exile. By mid-century, under Constantius (one of Constantine's sons), Arianism is actively favoured, with most of the influential positions in the church held by Arian bishops.

Over the years new middle ways are explored. Some suggest that the Son is 'of similar substance' (homoi-ousios) to the Father; others that he is 'like' Him (homoios). But eventually the debate runs out of steam - particularly when a pagan emperor, Julian the Apostate, concentrates the minds of the Christians by dismissing all their notions.

By AD 381, with a new generation of bishops and a new emperor, Theodosius, who is anti-Arian, the council summoned to Constantinople is in no mood for compromise. It conclusively rejects the Arian heresy and formally adopts a slightly modified version of the statement of faith promulgated at Nicaea. This AD 381 version is the text which becomes known as the Nicene creed.

And there the matter would seem, at first sight, to have ended. But it transpires that Arianism, like an irrepressible virus, has already spread elsewhere. The carrier is a remarkable man, Ulfilas, who in about 340 is appointed bishop to the barbarian Goths settled north of the Danube.

Ulfilas and his alphabet: AD c.360

Ulfilas is the first man known to have undertaken an extraordinarily difficult intellectual task - writing down, from scratch, a language which is as yet purely oral. He even devises a new alphabet to capture accurately the sounds of spoken Gothic, using a total of twenty-seven letters adapted from examples in the Greek and Roman alphabets.

God's work is Ulfilas' purpose. He needs the alphabet for his translation of the Bible from Greek into the language of the Goths. It is not known how much he completes, but large sections of the Gospels and the Epistles survive in his version - dating from several years before Jerome begins work on his Latin text.

Heresy and the barbarians: 4th - 6th century AD

Unfortunately for the cause of orthodoxy, the ministry of Ulfilas falls in the period when Arianism has its strongest following. Ulfilas himself subscribes to one of the milder versions, that which says Jesus is 'like' his Father. In this account the Trinity contains an element of hierarchy, with Jesus slightly below God and the Holy Spirit trailing both. It makes sense to the Goths, though most remain pagan till long after Ulfilas' death.

The Arian faith eventually becomes something of a national creed for the Germanic tribes. It is adopted, from the Goths, by the Vandals and by many other groups. And with the Germanic tribes on the move, in the upheavals of the 5th century, so Arianism spreads.

At various times in the 5th and 6th centuries, Italy is largely Arian under the Ostrogoths; Spain is Arian under the Visigoths; and north Africa is Arian under the Vandals.

The heresy is eliminated in most of these areas by the energetic campaigning of an orthodox emperor in Constantinople, Justinian. But another barbarian group, the Lombards, bring it back to north Italy in the late 6th century. In Visigothic Spain an Arian king is converted to orthodoxy in the 6th century and actively persecutes Arians from 589, but traces of the heresy remain until after the Muslims conquer in 711. By then the story has run for four centuries. Constantine, at Nicaea in 325, would not have approved.

Helvetian

History of the Helvetians

From about 500 B.C. to A.D. 400, several Celtic tribes, the most important of them named the Helvetians settled in Switzerland. They belonged to a family of nations that has been designated as Indo-Europeans because of evidently common roots in their languages that distinguish them from Asian, African or Semite (Arab, Hebrew) languages. Among the Indo-Europeans we find the Greeks, the Romans, Germanic and Slawonian tribes but as well parts of the Persian and Indian population. It has been assumed that the Indo-European tribes all came from the prairies of Southern Russia.

Oppidum of the Helvetians, Mount Vully, reconstructed section of ramparts

Unlike the prehistoric population of Switzerland the Helvetians preferred towns on hills to the open shore of lakes. Several Oppida [Oppidum = fortified Celtic city] of the Helvetians on hills have been excavated.

Culture of the Helvetians

Ancient Greek and Roman historians described the Celtic tribes as barbaric. Modern archeology has corrected this picture quite a bit. From excavations at La Tène on the shores of Lake Neuchâtel (western Switzerland, 1858) and many more in France, Germany and Austria we know that the Celts in central Europe had a highly developed culture. The Celtic cultural period Latène between 450 B.C. and 50 B.C. has been named after the excavations at La Tène.

Torques (Golden Celtic Collar) The Helvetians were skilled craftsmen, had highly developed technology in metal working and sense of style. They also knew how to organize work in pre-industrial manufactories. Celtic carts and wagons were even superior to Greek and Roman ones.

Were the Celts Barbarians?

Whether the Celtic habits to cry aloud when fighting or to collect cranes of killed enemies are more barbaric than the Roman habits to break treaties, take foreign diplomats as hostages and kill women and children in war (Cesar frankly admits that he often did so during his war against the Celts) and to let gladiators fight against wild animals in amphitheatres remains to be discussed. Other Greek and Roman arguments for Celtic barbarianism are just a matter of taste, not of civilization: the Celts did stiffen their hair with chalked water and they drank wine undiluted (while Greeks and Romans diluted it with water).

Austrian Celts traded with Greece; Swiss, French and Spanish Celts traded with Greek and Roman colonies in Southern France (Massilia = Marseille, Nice and others), Italy and Spain. They used Greek and Roman coins and coined their own later. At least a part of the Celtic population was able to read and write in Greek or Latin, but it seems they were not really interested in literature. So almost everything we know about the Celts (except for archeology) is written by Greek and Roman historians and commanders and insofar filtered through Greek and Roman prejudice.

What is worse: the scarce reports of these foreigners do not give insight into the spiritual world of the Celts. As a German proverb says "A picture tells more than a thousand words" - but it might as well nourish and lead astray the fantasy of those trying to interpret scenes engraved in pottery.

Bibracte: Helvetians vs. Romans

In 58 B.C. the Helvetians attempted to move south to Southern France. But they were stopped by the Roman commander and subsequent emperor C. Iulius Caesar near a Celtic town named Bibracte. Julius Cesar forced the Helvetians to return to Switzerland. Roman military camps and forts were erected at the northern Rhine frontier towards Germany to deter Germanic tribes from infiltration.

HELVETIA = Switzerland

The name of the Helvetians lived on in the Latin name of Switzerland, Helvetia during the Middle Ages, when Latin was used as a common European language for diplomacy and science. The Swiss Revolution of 1798 was first of all a rebellion against the supremacy of the founders of the Old Swiss Confederacy, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden and the cities of Lucerne, Zurich and Bern over the rest of the country. So it seems quite logical that the revolutionaries preferred the Latin name Helvetia to the colloquial name Schweiz (in German, derived from Schwyz) or Suisse (in French). Consequently they proclaimed the Helvetic Republic. The name was changed back again when the revolutionary experiment failed. In the Latin form it continued to exist, however.

Today, Helvetia is used as a keyword for Switzerland when a short name not depending on one of the four official languages spoken in different parts of Switzerland is needed.

Indians on the Inaugural March < Page 2 >

The issue facing all the chiefs and their respective peoples was the destruction of the Native American land base. The Dawes Act, initially passed in 1887, allowed for reservation lands—traditionally owned communally—to be divided among individual tribe members and their descendents. The available land was often inhospitable to traditional farming and the start-up costs of modern agriculture were beyond the means of many Indians.

The issue facing all the chiefs and their respective peoples was the destruction of the Native American land base. The Dawes Act, initially passed in 1887, allowed for reservation lands—traditionally owned communally—to be divided among individual tribe members and their descendents. The available land was often inhospitable to traditional farming and the start-up costs of modern agriculture were beyond the means of many Indians.

The act established a precedent that permitted the government to continue to survey and divide tribal lands, up until its termination in 1934.

In the years before the 1905 procession, tensions grew between Native peoples and white settlers over rights to natural resources. The prevailing notion was that the Indians would eventually sell their parcels and assimilate into the larger American society by moving elsewhere to ply their hands at other trades and over time, the notion of Indians would disappear. (Within two years of his participation in the parade, Quanah Parker’s tribal lands would be divided. Within 20 years, the Blackfeet would be dispossessed.)

Meanwhile, Geronimo did not have a home at all. He had been a prisoner of war since 1886 and he and several hundred of his fellow Apache were transported to barracks in Florida, Alabama and finally, in 1894, to Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Geronimo hoped that during his trip to Washington, D.C. he would be able to persuade Roosevelt to let him return to his homelands in the American southwest.

According to a contemporary account, Norman Wood’s Lives of Famous Indian Chiefs, the chiefs were granted an audience with the President a few days after the inauguration. Geronimo made his appeal through an interpreter. “Great Father,” he said, “my hands are tied as with a rope. My heart is no longer bad. I will tell my people to obey no chief but the great White Chief. I pray you cut the ropes and make me free. Let me die in my own country, an old man who has been punished long enough and is free.”

Citing his worries that tensions would erupt between Geronimo and the non-Indians who now occupied his lands, Roosevelt thought it best the old chief remain in Oklahoma. Geronimo would again plead his case for freedom through his autobiography, which was published in 1906 and dedicated to Roosevelt, but ultimately, he would die a prisoner.

The parade was over in the early evening, at which point the president and his party adjourned to the White House. The six chiefs’ presence in the parade exhibited their willingness to adapt to the changes imposed on their people as well as their resoluteness to maintain a sense of self and keep their cultural traditions alive. An exhibition commemorating the lives of these six men and their participation in the 1905 inaugural parade is on view at the National Museum of the American Indian until February 18, 2009. Page 2

Indians on the Inaugural March < Page 1 of 2 >

* By Jesse Rhodes

* Smithsonian.com, January 14, 2009

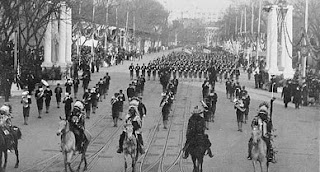

Elected to serve a full term as president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt—who initially took the oath of office after the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley—was about to enjoy his first inaugural parade. On March 4, 1905, he sat in the president’s box with his wife, daughter and other distinguished guests to watch the procession of military bands, West Point cadets and Army regiments—including the famed 7th Cavalry, Gen. George A. Custer’s former unit that fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn—march down Pennsylvania Avenue. Roosevelt applauded and waved his hat in appreciation and then suddenly, he and those is his company rose to their feet as six men on horseback came into view.

Elected to serve a full term as president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt—who initially took the oath of office after the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley—was about to enjoy his first inaugural parade. On March 4, 1905, he sat in the president’s box with his wife, daughter and other distinguished guests to watch the procession of military bands, West Point cadets and Army regiments—including the famed 7th Cavalry, Gen. George A. Custer’s former unit that fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn—march down Pennsylvania Avenue. Roosevelt applauded and waved his hat in appreciation and then suddenly, he and those is his company rose to their feet as six men on horseback came into view.

The men were all Indian chiefs—Quanah Parker (Comanche), Buckskin Charlie (Ute), American Horse (Sioux), Little Plume (Blackfeet), Hollow Horn Bear (Sioux) and Geronimo (Apache)—and each was adorned with face paint and elaborate feather headdresses that attested to their accomplishments. However, the causes they fought for over the course of their lifetimes were at odds with those of the American government.

Indeed, the newspapers of the day were quick to remind readers of the Indian wars, emphasizing the blood spilled by frontier settlers at the hands of Native Americans, going so far as to label them savages. Woodworth Clum, a member of the inaugural committee, questioned the president’s decision to have the chiefs participate, especially Geronimo, who was first captured by Clum’s father, an Apache agent.

“Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President? He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American history?” asked Clum.

“I wanted to give the people a good show,” was Roosevelt’s simple reply. But their inclusion in the parade was not without another purpose.

Flanking the chiefs were 350 cadets from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Capt. Richard Henry Pratt established the school in 1879 to “Americanize” Native American children, forcing them to abandon all facets of tribal culture. On arrival, students were re-clothed, renamed and began the process of being recast in the image of the dominant white culture, which involved everything from adopting the English language to being baptized under non-Native religions. Their presence in the 1905 inaugural parade was intended to showcase a new reality of Native American living. (Even American Horse had children at Carlisle, hoping that a Western education would allow them to better adapt to a rapidly changing world.)

“The driving idea about Native Americans,” says Jose Barreiro, a curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, "was represented by Colonel Pratt who was the head of the Carlisle Indian School and his famous phrase, 'Kill the Indian, save the man,' meaning take the culture out of the Indian.”

At best, the cadets received passing mention in the newspapers and nobody bothered to photograph them. All eyes were on the six chiefs. These men needed to be visible; for them, failure to remain in the public consciousness meant their people—and the problems they were facing—would be forgotten. “The Indian was ‘out of sight, out of mind’ at that point,” says Barreiro. “The notion in the 1900s was that the Indian was going to disappear—the vanishing American.”

Moghul

Babur in Kabul: AD 1504-1525 Babur, founder of the Moghul dynasty in India, is one of history's more endearing conquerors. In his youth he is one among many impoverished princes, all descended from Timur, who fight among themselves for possession of some small part of the great man's fragmented empire. Babur even captures Samarkand itself on three separate occasions, each for only a few months. The first time he achieves this he is only fourteen.

Babur, founder of the Moghul dynasty in India, is one of history's more endearing conquerors. In his youth he is one among many impoverished princes, all descended from Timur, who fight among themselves for possession of some small part of the great man's fragmented empire. Babur even captures Samarkand itself on three separate occasions, each for only a few months. The first time he achieves this he is only fourteen.

What distinguishes Babur from other brawling princes is that he is a keen oberver of life and keeps a diary. In it he vividly describes his triumphs and sorrows, whether riding out with friends at night to attack a walled village or mooning around for unrequited love of a beautiful boy.

Babur's 'throneless times', as he later describes these early years, come to an end in 1504 when he captures Kabul. Here, at the age of twenty-one, he is able to establish a settled court and to enjoy the delights of gardening, art and architecture in the Timurid tradition of his family.

With a powerful new Persian dynasty to the west (under Ismail I) and an aggressive Uzbek presence to the north (under Shaibani Khan), Babur's Kabul becomes the main surviving centre of the Timurid tradition. But these same pressures mean that his only chance of expanding is eastwards - into India.

Babur feels that he has an inherited claim upon northern India, deriving from Timur's capture of Delhi in 1398, and he makes several profitable raids through the mountain passes into the Punjab. But his first serious expedition is launched in October 1525.

Some forty years later (but not sooner than that) it is evident that Babur's descendants are a new and established dynasty in northern India. Babur thinks of himself as a Turk, but he is descended from Genghis Khan as well as from Timur. The Persians refer to his dynasty as mughal, meaning Mongol. And it is as the Moghul emperors of India that they become known to history.

Babur in India: AD 1526-1530

By the early 16th century the Muslim sultans of Delhi (an Afghan dynasty known as Lodi) are much weakened by threats from rebel Muslim principalities and from a Hindu coalition of Rajput rulers. When Babur leads an army through the mountain passes, from his stronghold at Kabul, he at first meets little opposition in the plains of north India.

The decisive battle against Ibrahim, the Lodi sultan, comes on the plain of Panipat in April 1526. Babur is heavily outnumbered (with perhaps 25,000 troops in the field against 100,000 men and 1000 elephants), but his tactics win the day.

Babur digs into a prepared position, copied (he says) from the Turks - from whom the use of guns has spread to the Persians and now to Babur. As yet the Indians of Delhi have no artillery or muskets. Babur has only a few, but he uses them to great advantage. He collects 700 carts to form a barricade (a device pioneered by the Hussites of Bohemia a century earlier).

Sheltered behind the carts, Babur's gunners can go through the laborious business of firing their matchlocks - but only at an enemy charging their position. It takes Babur some days to tempt the Indians into doing this. When they do so, they succumb to slow gunfire from the front and to a hail of arrows from Babur's cavalry charging on each flank.

Victory at Panipat brings Babur the cities of Delhi and Agra, with much booty in treasure and jewels. But he faces a stronger challenge from the confederation of Rajputs who had themselves been on the verge of attacking Ibrahim Lodi.

The armies meet at Khanua in March 1527 and again, using similar tactics, Babur wins. For the next three years Babur roams around with his army, extending his territory to cover most of north India - and all the while recording in his diary his fascination with this exotic world which he has conquered.

Humayun: AD 1530-1556

Babur's control is still superficial when he dies in 1530, after just three years in India. His son Humayun keeps a tentative hold on the family's new possessions. But in 1543 he is driven west into Afghanistan by a forceful Muslim rebel, Sher Shah.

Twelve years later, renewed civil war within India gives Humayun a chance to slip back almost unopposed. One victory, at Sirhind in 1555, is enough to recover him his throne. But six months later Humayun is killed in an accidental fall down a stone staircase. His 13-year-old son Akbar, inheriting in 1556, would seem to have little chance of holding on to India. Yet it is he who establishes the mighty Moghul empire.

Akbar: AD 1556-1605

In the early years of Akbar's reign, his fragile inheritance is skilfully held together by an able chief minister, Bairam Khan. But from 1561 the 19-year-old emperor is very much his own man. An early act demonstrates that he intends to rule the two religious communities of India, Muslim and Hindu, in a new way - by consensus and cooperation, rather than alienation of the Hindu majority.

In 1562 he marries a Rajput princess, daughter of the Raja of Amber (now Jaipur). She becomes one of his senior wives and the mother of his heir, Jahangir. Her male relations in Amber join Akbar's council and merge their armies with his.

This policy is very far from conventional Muslim hostility to worshippers of idols. And Akbar carries it further, down to a level affecting every Hindu. In 1563 he abolishes a tax levied on pilgrims to Hindu shrines. In 1564 he puts an end to a much more hallowed source of revenue - the jizya, or annual tax on unbelievers which the Qur'an stipulates shall be levied in return for Muslim protection.

At the same time Akbar steadily extends the boundaries of the territory which he has inherited.

Akbar's normal way of life is to move around with a large army, holding court in a splendid camp laid out like a capital city but composed entirely of tents. His biographer, Abul Fazl, describes this royal progress as being 'for political reasons, and for subduing oppressors, under the veil of indulging in hunting'.

A great deal of hunting does occur (a favourite version uses trained cheetahs to pursue deer) while the underlying political purpose - of warfare, treaties, marriages - is carried on.

Warfare brings its own booty. Signing a treaty with Akbar, or presenting a wife to his harem (his collection eventually numbers about 300), involves a contribution to the exchequer. As his realm increases, so does his revenue. And Akbar proves himself an inspired adminstrator.

The empire's growing number of provinces are governed by officials appointed only for a limited term, thus avoiding the emergence of regional warlords. And steps are taken to ensure that the tax on peasants varies with local circumstances, instead of a fixed proportion of their produce being automatically levied.

At the end of Akbar's reign of nearly half a century, his empire is larger than any in India since the time of Asoka. Its outer limits are Kandahar in the west, Kashmir in the north, Bengal in the east and in the south a line across the subcontinent at the level of Aurangabad. Yet this ruler who achieves so much is illiterate. An idle schoolboy, Akbar finds in later life no need for reading. He prefers to listen to the arguments before taking his decisions (perhaps a factor in his skill as a leader).

Akbar is original, quirky, wilful. His complex character is vividly suggested in the strange palace which he builds, and almost immediately abandons, at Fatehpur Sikri.

Fatehpur Sikri: AD 1571-1585

In 1571 Akbar decides to build a new palace and town at Sikri, close to the shrine of a Sufi saint who has impressed him by foretelling the birth of three sons. When two boys have duly appeared, Akbar's masons start work on what is to be called Fatehpur ('Victory') Sikri. A third boy is born in 1572.

Akbar's palace, typically, is unlike anyone else's. It resembles a small town, made up of courtyards and exotic free-standing buildings. They are built in a linear Hindu style, instead of the gentler curves of Islam. Beams and lintels and even floorboards are cut from red sandstone and are elaborately carved, much as if the material were oak rather than stone.

The palace and mosque occupy the hill top, while a sprawling town develops below. The site is only used for some fourteen years, partly because Akbar has overlooked problems of water supply. Yet this is where his many and varied interests are given practical expression.

Here Akbar employs translators to turn Hindu classics into Persian, scribes to produce a library of exquisite manuscripts, artists to illustrate them (the illiterate emperor loves to be read to and takes a keen interest in painting). Here there is a department of history under Abul Fazl; an order is sent out that anyone with personal knowledge of Babur and Humayun is to be interviewed so that valuable information is not lost.

The building most characteristic of Akbar in Fatehpur Sikri is his famous diwan-i-khas, or hall of private audience. It consists of a single very high room, furnished only with a central pillar. The top of the pillar, on which Akbar sits, is joined by four narrow bridges to a balcony running round the wall. On the balcony are those having an audience with the emperor.

If required, someone can cross one of the bridges - in a respectfully crouched position - to join Akbar in the centre. Meanwhile, on the floor below, courtiers not involved in the discussion can listen unseen.

In the diwan-i-khas Akbar deals mainly with affairs of state. To satisfy another personal interest, in comparative religion, he builds a special ibabat-khana ('house of worship'). Here he listens to arguments between Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Zorastrians, Jews and Christians. The ferocity with which they all attack each other prompts him to devise a generalized religion of his own (in which a certain aura of divinity rubs off on himself).

The Christians involved in these debates are three Jesuits who arrive from Goa in 1580. As the first Europeans at the Moghul court, they are a portent for the future.

Jahangir: AD 1605-1627

Akbar is succeeded in 1605 by his eldest and only surviving son, Jahangir. Two other sons have died of drink, and Jahangir's effectiveness as a ruler is limited by his own addiction to both alcohol and opium. But the empire is now stable enough for him to preside over it for twenty-two years without much danger of upheaval.

Instead he is able to indulge his curiosity about the natural world (which he records in a diary as vivid as that of his great-grandfather Babur) and his love of painting. Under his keen eye the imperial studio brings the Moghul miniature to a peak of perfection, maintained also during the reign of his son Shah Jahan.

Moghul miniatures: 16th - 17th century AD

When Humayun wins his way back into India, in 1555, he brings with him two Persian artists from the school of Bihzad. Humayun and the young Akbar take lessons in drawing. Professional Indian artists learn too from these Persian masters.

From this blend of traditions there emerges the very distinctive Moghul school of painting. Full-bodied and realistic compared to the more fanciful and decorative Persian school, it develops in the workshops which Akbar establishes in the 1570s at Fatehpur Sikri.

Akbar puts his artists to work illustrating the manuscripts written out by scribes for his library. New work is brought to the emperor at the end of each week. He makes his criticisms, and distributes rewards to those who meet with his approval.

Detailed scenes are what Akbar likes, showing court celebrations, gardens being laid out, cheetahs released for the hunt, forts being stormed and endless battles. The resulting images are a treasure trove of historical detail. But as paintings they are slightly busy.

Akbar's son Jahangir takes a special interest in painting, and his requirements differ from his father's. He is more likely to want an accurate depiction of a bird which has caught his interest, or a political portrait showing himself with a rival potentate. In either case the image requires clarity and conviction as well as finely detailed realism.

The artists rise superbly to this challenge. In Jahangir's reign, and that of his son Shah Jahan, the Moghul imperial studio produces work of exceptional beauty. In Shah Jahan's time even the crowded narrative scenes, so popular with Akbar, are peopled by finely observed and convincing characters.

Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb: AD 1627-1707

During the reigns of Shah Jahan and his son Aurangzeb, the policy of religious toleration introduced by Akbar is gradually abandoned. It has been largely followed by Shah Jahan's father, Jahangir - though at the very start of his reign he provides the Sikhs with their first martyr when the guru Arjan is arrested, in 1606, and dies under torture.

In 1632 Shah Jahan signals an abrupt return to a stricter interpretation of Islam when he orders that all recently built Hindu temples shall be destroyed. A Muslim tradition states that unbelievers may keep the shrines which they have when Islam arrives, but not add to their number.

Direct provocation of this kind is untypical of Shah Jahan, but it becomes standard policy during the reign of his son Aurangzeb. His determination to impose strict Islamic rule on India undoes much of what was achieved by Akbar. An attack on Rajput territories in 1679 makes enemies of the Hindu princes; the reimposition of the jizya in the same year ensures resentment among Hindu merchants and peasants.

At the same time Aurangzeb is obsessed with extending Moghul rule into the difficult terrain of southern India. He leaves the empire larger but weaker than he finds it. In his eighties he is still engaged in permanent and futile warfare to hold what he has seized.

In the decades after the death of Aurangzeb, in 1707, the Moghul empire fragments into numerous semi-independent territories - seized by local officials or landowners whose descendants become the rajas and nawabs of more recent times. Moghul emperors continue to rule in name for another century and more, but their prestige is hollow.

Real power has declined gradually and imperceptibly throughout the 17th century, ever since the expansive days of Akbar's empire. Yet it is in the 17th century that news of the wealth, splendour, architectural brilliance and dynastic violence of the Moghul dynasty first impresses the rest of the world.

Europeans become a significant presence in India for the first time during the 17th century. They take home descriptions of the ruler's fabulous wealth, causing him to become known as the Great Moghul. They have a touching tale to tell of Shah Jahan's love for his wife and of the extraordinary building, the Taj Mahal, which he provides for her tomb.

And as Shah Jahan's reign merges into Aurangzeb's, they can astonish their hearers with an oriental melodrama of a kind more often associated with Turkey, telling of how Aurangzeb kills two of his brothers and imprisons his ageing father, Shah Jahan, in the Red Fort at Agra - with the Taj Mahal in his view across the Jumna, from the marble pavilions of his castle prison.

Moghul domes: AD 1564-1674

The paintings commissioned by the Moghul emperors are superb, but it is their architecture which has most astonished the world - and in particular the white marble domes characteristic of the reign of Shah Jahan.

There is a long tradition of large Muslim domes in central Asia, going as far back as a tomb in Bukhara in the 10th century. But the Moghuls develop a style which is very much their own - allowing the dome to rise from the building in a swelling curve which somehow implies lightness, especially when the material of the dome is white marble.

The first dome of this kind surmounts the tomb of Humayun in Delhi, built between 1564 and 1573. The style is then overlooked for a while - no doubt because of Akbar's preference for Hindu architecture, as in Fatehpur Sikri - until Shah Jahan, the greatest builder of the dynasty, develops it in the 17th century with vigour and sophistication.

His first attempt in this line is also his masterpiece - a building which has become the most famous in the world, for its beauty and for the romantic story behind its creation.

Throughout his early career, much of it spent in rebellion against his father, Shah Jahan's greatest support has been his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. But four years after he succeeds to the throne this much loved companion dies, in 1631, giving birth to their fourteenth child. The Taj Mahal, her tomb in Agra, is the expression of Shah Jahan's grief. Such romantic gestures are rare among monarchs (the Eleanor Crosses come to mind as another), and certainly none has ever achieved its commemorative purpose so brilliantly.

There is no known architect for the Taj. It seems probable that Shah Jahan himself takes a leading role in directing his masons - particularly since his numerous other buildings evolve within a related style.

The Taj Mahal is built between 1632 and 1643. In 1644 the emperor commissions the vast Friday Mosque for his new city in Delhi. In 1646 he begins the more intimate Pearl Mosque in the Red Fort in Agra. Meanwhile he is building a new Red Fort in Delhi, with white marble pavilions for his own lodgings above massive red sandstone walls. At Fatehpur Sikri he provides a new shrine for the Sufi saint to whom his grandfather, Akbar, was so devoted.

All these buildings contain variations on the theme of white and subtly curving domes, though none can rival Shah Jahan's first great example in the Taj.

Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan's son, does not inherit his father's passionate interest in architecture. But he commissions two admirable buildings in the same tradition. One is the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, begun in 1673; even larger than his father's Friday Mosque in Delhi, it rivals it in the beauty of its domes. The other, begun in 1662, goes to the other extreme; the tiny Pearl Mosque in the Red Fort in Delhi, begun in 1662 for Aurangzeb's private worship, is a small miracle of white marble.

It is these marble highlights which catch the eye. But the Red Forts containing the two Pearl Mosques are themselves extraordinary examples of 17th century castles.

The Moghuls after Aurangzeb: 18th century AD

When the Moghul emperor Aurangzeb is in his eighties, and the empire in disarray, an Italian living in India (Niccolao Manucci) predicts appalling bloodshed on the old man's death, worse even than that which disfigured the start of Aurangzeb's reign. The Italian is right. In the war of succession which begins in 1707, two of Aurangzeb's sons and three of his grandsons are killed.

Violence and disruption is the pattern of the future. The first six Moghul emperors have ruled for a span of nearly 200 years. In the 58 years after Aurangzeb's death, there are eight emperors - four of whom are murdered and one deposed.

This degree of chaos has a disastrous effect on the empire built up by Akbar. The stability of Moghul India depends on the loyalty of those ruling its many regions. Some are administered on the emperor's behalf by governors, who are members of the military hierarchy. Others are ruled by princely families, who through treaty or marriage have become allies of the emperor.

In the 18th century rulers of each kind continue to profess loyalty to the Moghul emperor in Delhi, but in practice they behave with increasing independence. The empire fragments into the many small principalities whose existence will greatly help the British in India to gain control, by playing rival neighbours off against each other.

In the short term, though, there is a more immediate danger. During the 1730s a conqueror in the classic mould of Genghis Khan or Timur emerges in Persia. He seizes the Persian throne in 1736, taking the title Nadir Shah.

Later that year he captures the stronghold of Kandahar. The next major fortress on the route east, that of Kabul, is still in Moghul hands - a treasured possession since the time of Babur. Nadir Shah takes it in 1738, giving him control of the territory up to the Khyber Pass. Beyond the Khyber lies the fabulous wealth of India. Like Genghis Khan in 1221, and Timur in 1398, Nadir Shah moves on.

In December 1738 Nadir Shah crosses the Indus at Attock. Two months later he defeats the army of the Moghul emperor, Mohammed Shah. In March he enters Delhi. The conqueror has iron control over his troops and at first the city is calm. It is broken when an argument between citizens and some Persian soldiers escalates into a riot in which 900 Persians are killed. Even now Nadir Shah forbids reprisals until he has inspected the scene. But when he rides through the city, stones are thrown at him. Someone fires a musket which kills an officer close to the shah.

In reprisal he orders a massacre. The killing lasts for a day. The number of the dead is more than 30,000.

Amazingly, when the Moghul emperor begs for mercy for his people, the Persian conqueror is able to grant it. The killing stops, for the collection of Delhi's valuables to begin.